Graffiti: the stories we tell

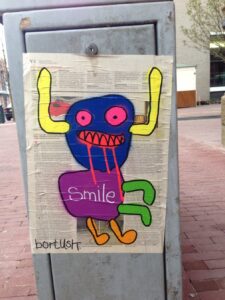

I found a new Bortusk poster in Amsterdam today. A slightly torn and weathered neon monster staring out at me from the side of a skip as i cycled past. I think that brings to about fifteen the number i’ve found around the city this year. Sometimes i go back to visit them, watching as the paper gets more torn, dirtier, overlaid with graffiti and stickers, or simply weathered away by the Dutch climate.

Bortusk is enigmatic: his colourful monsters placed seemingly for no other reason than to brighten up your day, a task they fulfil perfectly for me as they smile, wave and dance into sight on a rainy morning as you cycle past. For some, they are probably just graffiti: rubbish cluttering the street. For others, something to make you smile.

For me, they tell a story: a story about creativity, about sharing, about meaning. Once placed, they fall out of control of the artist, much as any story we publish moves beyond our control. Once curated, stuck into place, they become part of our environment, open to interpretation and reinterpretation as we please. It must have been six months ago that i found the first one, staring out at me and saying ‘smile‘, which i did. Then, over the following weeks, i found more and more members of the family, before i ever knew who they were by or what their history was. For me, they were just random moments of neon tinted welcome strewn around a strange city.

We create meaning in the world around us: we join the dots. No story is complete until we have read it, until we have made it our own and imposed our own meaning upon it. This is true of factual or fictional stories, stories we use at work, read on the train or tell to our children. The act of the telling and the reading change the meaning.

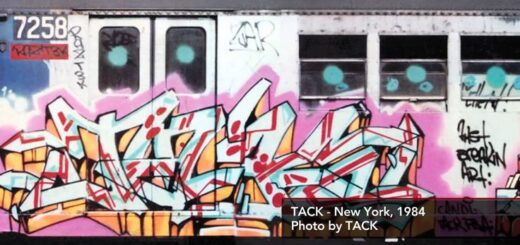

Graffiti is the unofficial language of society: the voice for the voiceless, or those who don’t want to be known. Sometimes it carries political messages, sometimes it’s about tagging territory or establishing hierarchies of importance and power, sometimes it’s hostile and threatening. There is a vocabulary of graffiti that may not be known to those of us outside the circle.

Stories are not static: as graffiti grows over time, is overlain with new meaning, is replaced and stratified, so too do stories grow. We can lay the foundations, we can make the first telling, but as they spread through communities and are retold ad infinitum they change, they become owned by the communities that share them.

The narrative is important, the words that surround it less so. The meaning is what will persist if it is relevant and clear, so when we craft our stories, like posters on a wall, they need to be clear, but we have to recognise that they will move out of our control. And, eventually, they will weather and fade, becoming simply the foundations for the next chapter that is built upon them.